Constitutional Convention and Prior Attempts

The Constitutional Convention: Learning from Prior Attempts to Forge a Lasting Union

Introduction:

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 is renowned for the creation of the United States Constitution. Yet, it is crucial to recognize that this convention did not emerge out of thin air. It was shaped by the experiences and lessons learned from prior attempts at establishing a strong and enduring union. In this article, we will explore some key historical events leading up to the Constitutional Convention, highlighting the Articles of Confederation, Shays' Rebellion, and the Annapolis Convention, and how they influenced the subsequent gathering in Philadelphia.

The Flawed Articles of Confederation:

Before the Constitutional Convention, the newly independent United States operated under the Articles of Confederation. Adopted in 1781, these articles established a weak central government with limited powers and no executive branch. The lack of a unified economic policy, challenges in raising revenue, and the inability to enforce laws effectively became evident, leading to dissatisfaction among the states. This realization prompted the need for a reevaluation of the current system.

Shays' Rebellion and its Impact:

Shays' Rebellion, which occurred in Massachusetts from 1786 to 1787, was a significant event in signaling the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. Led by farmers burdened by debt and high taxes, this armed uprising highlighted the government's inability to quell domestic unrest and raised concerns about the fragility of the union. The rebellion underscored the necessity for a stronger central government capable of maintaining law and order.

The Annapolis Convention's Call for Action:

In response to the economic and political challenges faced by the young nation, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison organized the Annapolis Convention in 1786. Although attendance was limited, the convention served as a catalyst for change by addressing trade issues among the states. Recognizing the need for broader reforms, the delegates issued a call for a larger constitutional convention to be held the following year in Philadelphia.

The Constitutional Convention:

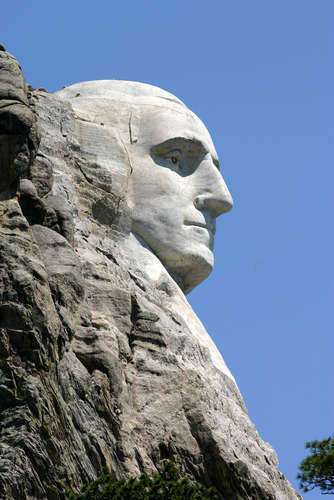

Convened in 1787, the Constitutional Convention comprised delegates from twelve states (Rhode Island abstained). Some influential figures present were George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison. Building upon the failures of the Articles of Confederation and the lessons learned from previous events, the delegates debated and crafted a new framework for governance.

Learnings and Key Debates:

The debates at the Constitutional Convention centered on crucial issues, such as balancing power between the federal and state governments, representation, and slavery. The structure of the new government's branches, the establishment of checks and balances, and the protection of individual rights were also fiercely discussed. Through intense deliberations and compromises, including the Connecticut Compromise and the Three-Fifths Compromise, the framers of the Constitution sought to address these contentious matters.

The Legacy of the Constitutional Convention:

The Constitutional Convention's ultimate achievement was the creation of the United States Constitution, which laid the foundation for a durable democratic republic. The Constitution, ratified in 1788, established the framework for a stronger central government while safeguarding individual liberties. Its longevity and adaptability have proven essential as the nation has evolved over the centuries.

Conclusion:

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was the culmination of an evolving understanding of the challenges faced by the young United States. Prior attempts, such as the Articles of Confederation, Shays' Rebellion, and the Annapolis Convention, provided valuable insights into the flaws of the preceding systems. The delegates, armed with this knowledge, worked diligently to address these shortcomings and craft a more perfect union. Today, we recognize the Constitutional Convention as a testament to the Founding Fathers' commitment to learning from the past and forging a lasting democratic republic.

Even prior to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, as a result of the chaos that ensued as a result of the flawed gubernatorial model established in Articles of Confederation, a complete adjustment of the national legislative schematic was already set in motion by not only Federalists Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, but also by figureheads such as Benjamin Franklin and George Washington.

A conference was held in Mt. Vernon, Virginia in 1785 in order to determine a course of action for the circumvention of the Potomac River. Due to the Articles of Confederation’s vague criterion concerning interstate legislation, which ultimately disallowed the establishment of determining any sort of State borders in regards to the Potomac River, which spanned across multiple states, such as Maryland and Virginia, it became clear that the governmental system needed to be reevaluated. As a result, the delegates at the conference proposed a nationwide convention in Philadelphia with the hopes of completely reformatting the existing governmental schematic. This was known as the Constitutional Convention.

The Constitutional Convention began at Independence Hall in Philadelphia on May 5th, 1787, and ended up on the completion of the final draft of the Constitution on September 17th, 1787. The Constitutional Convention was comprised of 55 delegates from 12 of the 13 states of the Union; Rhode Island, protesting the proposed ideals set forth in the Constitution, refused to send any delegates.

The Constitutional Convention was presided over by George Washington, a delegate from Virginia, and the future first President of the United States. The actual content of the Constitution is considered to be a conglomeration of ideas contributed by various politicos of that time, including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Thomas Paine, and John Adams.

Despite an initial desire to simply modify the precepts set forth in the Articles of Confederation, the delegates participating in the Constitutional Convention found the existing gubernatorial and legislative systems unworkable, and as a result, created an entirely new document, which would become the Constitution of the United States. Rhode Island’s vehement opposition of the abolition of the Articles of Confederation prompted their refusal to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention.

The legislative methodology set forth in the Articles of Confederation maintained that an amendment of legislation, which was precisely the purpose of the Constitutional Convention, could not take place without the unanimous approval of each of the 13 states of the Union. Yet, the refusal to participate on the part of Rhode Island’s State legislature was perceived to be laden with irony by the Federalists. The Federalists maintained that a single State’s ability to sway a decision on a national scale was inherently paradoxical.

However, even without the participation of Rhode Island, the Constitutional Convention commenced. The remaining 12 states grew tired of perpetual legislative ambiguity and erratic trade policies. The Constitutional Convention would cover a host of issues, both legislative and commercial, such as the role of the central government, State representation, taxes, tariffs, the establishment of borders, and slavery.